Tutorial Categories

Last Updated: January 15, 2026 at 09:30

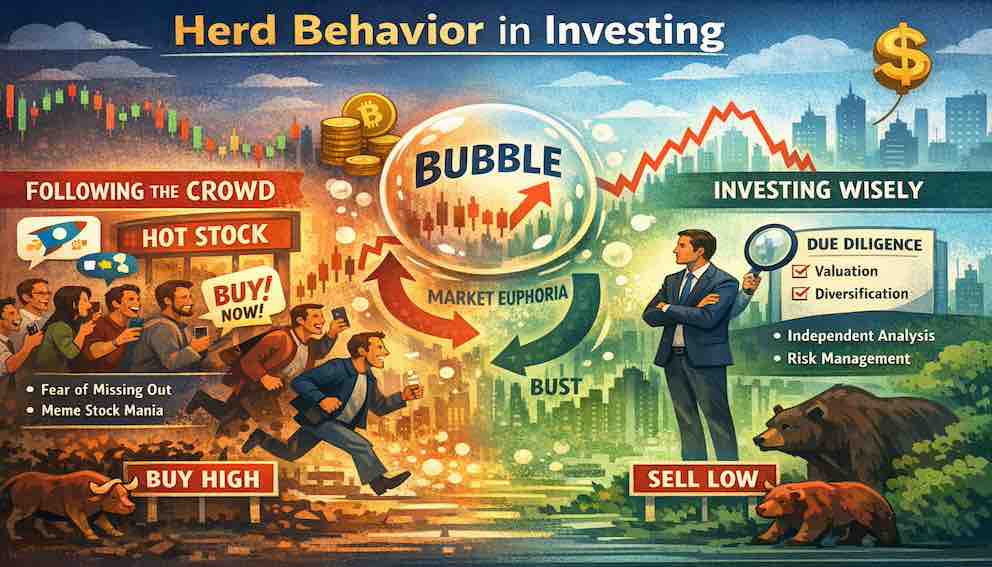

Herd Behavior: Why Following the Crowd Feels Safe - Behavioral Finance Series

Why do investors rush into the hottest stocks or panic sell during market drops? Herd behavior—the tendency to follow the crowd—can drive buying frenzies, market bubbles, and sharp crashes. In this tutorial, we explore the psychology behind herding, the difference between rational and emotional crowd behavior, real-world examples from GameStop to the dot-com bubble, and expert strategies to recognize, mitigate, and even use herd behavior wisely in your investing.

Imagine this: You’ve been following a stock quietly rising for months. One morning, headlines are full of it. Your friends and colleagues are talking about it. Social media is buzzing. “Am I missing out?” you wonder. You buy in—only to watch the stock fall shortly after.

This is a classic example of herd behavior: the strong pull to follow what others are doing, even if your own analysis says otherwise. Ironically, doing what feels safe—copying the crowd—can sometimes be the riskiest choice.

Core Theory

What is Herd Behavior?

Herd behavior happens when people mimic the actions of others, often ignoring their own information or judgment. In investing, it shows up as buying what everyone else is buying, selling when others panic, or avoiding contrarian decisions.

Why We Herd

Humans are social creatures, and investing is no exception. Herd behavior happens because our brains are wired to follow others, especially when the situation feels uncertain or risky. Here are the main reasons we herd:

- Social Proof – We often assume that if many people are doing something, it must be right. For example, if a stock suddenly appears on every financial news headline and everyone around you is buying, it feels safer to join in, even if your research is incomplete. Social proof is why trends and “hot picks” gain momentum so quickly.

- Fear of Standing Out – Going against the crowd feels risky. Making a unique decision—like holding cash when everyone else is buying tech stocks—can be uncomfortable. Failing alone hurts more psychologically than failing with others. Think of it like a student in class who doubts a teacher’s solution but stays quiet because everyone else agrees; the same dynamic happens in investing.

- Information Cascades – Sometimes we see others acting as if they know something we don’t, and we assume they are better informed. Even if you have private information suggesting otherwise, the visible actions of others can make you ignore your own signals. A classic example: early investors in a startup buy shares based on seeing a line of other investors waiting—eventually, everyone piles in, sometimes inflating the price far above real value.

Rational vs. Irrational Herding

Herding isn’t always just emotional. Researchers distinguish between rational and emotional types:

- Informational Cascades (Rational Herding) : Even rational investors can herd if they think others have better information. Banerjee (1992) and Bikhchandani et al. (1992) showed that in situations with limited data, individuals may ignore their private signals and follow the crowd. This can lead to collective irrationality—even though each decision alone seems reasonable.

Example: Early adopters of a new tech stock buy because they believe insiders know something, leading more investors to follow and drive up the price beyond fundamentals.

- Reputational Herding (Rational Herding) : Professionals often herd to protect their careers. It is safer to fail with the crowd than alone. Institutional investors frequently show this through benchmark-hugging or joining consensus trades.

Example: During the late-1990s tech boom, many fund managers invested heavily in dot-com companies to avoid underperforming peers—even if they privately doubted valuations.

- Irrational/Emotional Herding : This is pure social contagion: fear of missing out (FOMO), excitement over “hot stocks,” or panic selling. It’s driven by emotion rather than information.

Example: Retail investors buying meme stocks like GameStop or AMC simply because everyone on social media was talking about them, ignoring valuations or long-term risks.

Understanding these distinctions helps investors see why herding happens, not just that it does. Some herding is rational and unavoidable, while other types are purely emotional—and that awareness is the first step to making smarter investment decisions.

Financial Consequences

Impact on Individual Investors

- Buying at Peaks – Meme stock mania (GameStop, AMC) and crypto surges show how FOMO can lead to losses.

- Panic Selling – March 2020’s COVID crash is an example of the herd rushing for the exits.

Portfolio Implications

- Herding can cause overconcentration in trending sectors, reducing diversification.

- It may turn a long-term strategy into reactive, emotional trading.

Market Effects

- Price Distortions & Reduced Efficiency – Herding can push prices far from fundamental value for long periods. This can create opportunities for contrarian investors but introduces systemic risk for the herd.

- Liquidity Illusions & Flash Crashes – During booms, everyone is buying, creating a false sense of liquidity. A sudden reversal can trigger a massive sell-off, as in the 2010 Flash Crash.

- The “Greater Fool” Theory – Herding often fuels bubbles: investors buy overvalued assets expecting to sell them to someone less informed (“the greater fool”).

Real-Life Example

During the dot-com bubble, investors bought almost any company with a “.com” in its name, ignoring earnings or revenue. Nasdaq 100 rose over 400% between 1995–2000, then crashed 78% by 2002. Herd behavior magnified both the rise and the fall.

Expert vs Novice Behavior

Novice Investors

- Follow headlines, social media, or peer actions

- Rarely check valuations, diversification, or risk exposure

- Decisions driven by emotion rather than process

Experts and Professionals

- Not immune – Institutional investors herd too, often due to reputational risk

- Framework-driven – True experts assess why the crowd is moving: fundamentals or sentiment

- Use the herd as data – They see crowd behavior as a signal, not instruction

- Disciplined processes – Checklists, valuation criteria, risk limits, and peer review reduce emotional bias

Example

A professional fund manager may avoid a hot tech stock if it violates risk rules, even when the buzz is overwhelming. The crowd can inform their market sentiment analysis but not dictate actions.

Practical Mitigation Strategies

- Predefined Decision Rules – Set buy/sell criteria based on valuation, not headlines.

- Automation – Robo-advisors, index funds, and rules-based strategies reduce FOMO-driven trades.

- Diversification & Position Limits – Avoid overweighting hot sectors or single stocks.

- Independent Verification – Conduct personal research and compare with historical trends.

- Reflective Journaling – Track decisions and motivations to spot herding patterns in your own behavior.

Nuance & Debate

- When Herding is Rational – Following standardized practices, like accounting rules or index fund investing, reduces transaction costs and provides market coherence.

- The Contrarian Challenge – Acting against the herd is psychologically and financially difficult. Keynes’ warning remains relevant: “The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.” Mitigating herding requires conviction, risk management, and a long horizon.

- Joining the herd in the early stages of herd behavior can be rewarding(e.g. 1999 stock market rally, 2025 stock market rally).

- Positive Herding – Some herd-like behavior, such as investing in diversified index funds, is beneficial, providing safety, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness.

Clear Takeaway

Herd behavior is a natural human instinct, but unchecked, it can erode returns and amplify risk. The goal is not to eliminate emotion, but to use structured frameworks and reflective habits to prevent the herd from silently driving your decisions.

Reflective Prompt:

Next time a stock or asset class is surging, ask yourself: Am I buying because I’ve analyzed it, or because everyone else is? Your answer will reveal whether you are thinking independently—or following the herd.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.