December 30, 2025 at 11:39

U.S. Federal Debt at a Crossroads: Inflation, Interest, and the Fiscal Challenge Ahead

Authored by MyEyze Finance Desk

The scale and speed of accumulation of the U.S. government’s debt have crossed into territory many economists—and a growing number of investors—consider unsustainable. With borrowing increasing on multiple fronts, interest costs soaring, and signs that traditional buyers of U.S. debt may be pulling back, the fiscal foundations of the world’s largest economy look increasingly fragile. Below is a sober assessment of where things stand—and what the consequences could be if Washington does not act.

A Debt Mountain: How Big — and How Fast

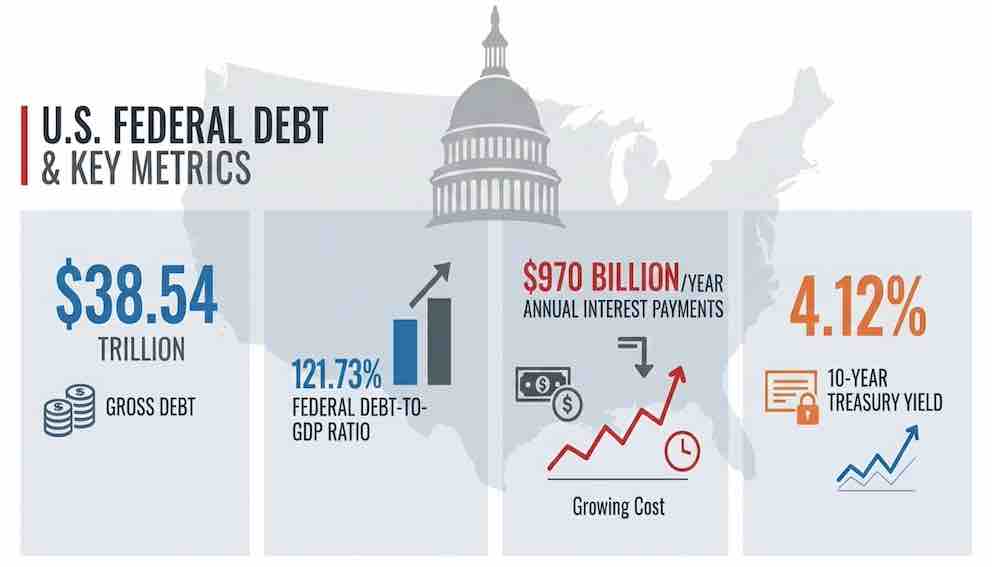

As of late december 2025, the gross national debt of the United States stood at about $38.54 trillion. That number has risen dramatically — over one year it increased by roughly $2.3 trillion. Meanwhile, on a per-person basis, the debt burden is staggering: about $111,986 per American (or nearly $280,000 per household).

Debt-to-GDP: A Critical Ratio

Viewed in relation to the U.S. economy, the ratio is deeply concerning. Using nominal GDP estimates, federal debt-to-GDP exceeds 121.73, meaning the federal debt exceeds the total annual value of goods and services produced in a year. In short: the U.S. is borrowing more, faster, and now carries more debt than at any time in its history.

Borrowing Costs: The New Budget Monster

Debt itself is a problem—but the mounting cost to service that debt is rapidly becoming a national financial burden. In fiscal year 2025, net interest payments on U.S. debt reached roughly $970 billion, or about 13% of total federal spending — the highest share in 25 years. To put that into perspective: interest payments now exceed what the U.S. spends on national defense — one of the largest discretionary budget items.

Underlying this increase is a rise in interest rates. As of late 2025, 10-year Treasury yields are hovering around 4.12%, reflecting broader market conditions. As long as interest rates remain elevated — and as the government continues to borrow — the cost of rolling over and servicing the debt will grow. That represents a structural headwind for fiscal sustainability.

The Shifting Landscape of Debt Holders

A Potential Funding Gap

Recent data suggests foreign demand is softening — China, for example, has reduced its holdings in recent months and demand from Japan is falling. That begs the question: who will absorb the next increments of borrowing? The burden may increasingly fall on domestic investors — including pension funds, mutual funds, and the central bank — a shift with potential long-term implications.

Key Factors Driving Unsustainability

- The “Interest-Expense Squeeze” on Essential Spending: As interest payments soak up an ever larger share of the budget, critical government functions — from infrastructure to education, from social welfare to climate investment — risk being crowded out. Indeed, without serious reforms, projections suggest debt interest could consume upwards of a fifth of federal revenue over the next decade.

- Growing Dependence on Domestic — and Possibly Less Stable — Buyers: If foreign investors retreat, the U.S. will increasingly rely on domestic buyers to fund its deficits. Such a shift risks undermining confidence in Treasuries and might impair the dollar’s status as a reserve currency.

- Borrowing from the Future — With Compounding Consequences: Essentially, current generations are financing their consumption, investments and social programmes by pushing the financial burden onto future generations. That may require future governments to choose between painful options: reduce spending, increase taxes, or accept slower economic growth.

- Inflation Risk — And the Temptation to “Inflate Away” Debt: With heavy borrowing, there’s always the temptation to rely on inflation as a stealth tax. But that approach carries serious risks. Persistent inflation erodes consumers’ purchasing power and when central banks eventually tighten in response, higher rates further increase interest costs.

- Weakening of the U.S. Fiscal Safety Margin: Large sovereign debt in itself is not necessarily dangerous — if the borrower enjoys strong economic growth, stable financing, and confidence in its currency. But when debt accumulates rapidly, interest costs rise, and foreign demand softens, that margin of safety shrinks.

What the U.S. Could Learn (And Borrow) from the UK’s Debt-Strain Experience

The Clear Lesson for the U.S.

Why So Far It’s Worked — But for How Long?

Eroding Supports and Emerging Risks

The Price of Inaction — And the Stakes

- Interest costs could balloon further, becoming the dominant federal outlay — crowding out spending on infrastructure, education, climate, social welfare, and innovation.

- Economic growth could slow as private investment is “crowded out” by high interest rates, while taxes may have to rise and public spending shrink.

- Fiscal flexibility — the ability to respond to recessions, crises or emergencies — would be sharply curtailed.

- Intergenerational equity would suffer most: future Americans would inherit the bill, while today’s generation enjoys the benefits.

- Moreover, continued high debt could erode confidence in the dollar, threaten the appeal of U.S. debt as a global safe asset, and ultimately undercut U.S. global financial leadership.

What Must Be Done — Painful but Necessary Steps

- Fiscal consolidation — that means rethinking entitlement growth, defence spending, and discretionary budgets. Not just across-the-board cuts, but structural reform to ensure long-run sustainability.

- Tax reform — broadening the tax base, closing loopholes, and ensuring that tax policy supports long-term growth rather than short-term political gains.

- Debt/spending rule or framework — similar to “fiscal rules” in other advanced economies: a mechanism that constrains deficits over an economic cycle.

- Debt maturity management — responsibly managing the maturity profile of outstanding debt to avoid bunching of refinancing at high rates, and reducing reliance on short-term borrowing.

- Promoting economic growth — productivity-enhancing investments (infrastructure, education, research) that can raise GDP over time, lifting the denominator in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

The Political Reality

5-Year and 10-Year Stress-Test Scenarios

Five year stress test

If the U.S. maintains annual deficits in the current range (roughly $1.5–$2 trillion) and average interest rates stay near today’s levels (4–4.5 %), total federal debt could reach $45–$50 trillion by 2030. Crucially, interest costs would compound rapidly: even without higher rates, annual net interest could rise from about $880 billion to $1.2–$1.5 trillion by 2030, consuming a growing share of federal revenue. Under this stress scenario, interest spending alone would approach or exceed the entire defense budget and potentially rival Social Security as a major outlay. Debt-to-GDP would likely rise into the 135–150% range unless real economic growth strengthens materially. This would mark a transition from “high but manageable debt” to a phase where markets begin questioning U.S. fiscal discipline, making Treasury auctions more sensitive to weak demand or foreign pullback.

Ten year stress test

Over a decade, the compounding effect becomes much more dangerous. Assuming deficits remain elevated and average borrowing costs drift up only modestly to the 4.5–5% range as debt supply increases, total federal debt could plausibly reach $55–$60+ trillion by 2035. Net interest spending could cross $2 trillion annually, turning interest into the single largest line item in the federal budget and crowding out discretionary spending on infrastructure, education, defence, and scientific research. Debt-to-GDP could drift toward 150–170%, levels typically associated with fiscal stress in advanced economies. In this stress case, a negative feedback loop emerges: higher debt → higher interest cost → higher deficits → more borrowing → further market anxiety about sustainability. This would severely reduce the government’s ability to respond to recessions, financial shocks or geopolitical crises, and could eventually pressure the dollar’s reserve-currency premium if investors demand significantly higher yields or diversify into non-U.S. assets.

A Structural Risk, Not a Distant Problem

The U.S. government’s debt burden, once a manageable tool for smoothing economic cycles and funding strategic investments, has morphed into a structural risk. With a debt load exceeding $38.5 trillion, a debt-to-GDP ratio above 121%, interest payments already outpacing defense spending, and signs that foreign support may be weakening, the path ahead is narrow and perilous. While a sovereign default remains unlikely — the U.S. can always print dollars to meet its obligations — the bigger risk is that the debt is being inflated away, eroding the real value of savings, investments, and income, and potentially destabilizing the economy over time.

Conclusion

The repercussions of such high level of debt — higher taxes, slower growth, weaker public services, and increased economic vulnerability — will unfold over the next decade and ultimately be borne by future generations. Federal debt is growing by roughly $2.2 trillion each year(probably more as per some sources), and some projections suggest it could reach around $59 trillion by 2035 under current policy assumptions. Even without additional policy changes, debt is expected to continue rising as government spending outpaces revenue.

Foreign investors’ share of U.S. Treasury holdings has declined in recent years as total debt has grown faster than foreign purchases, meaning a larger portion of financing must come from domestic sources. Heavy reliance on domestic financing could put pressure on financial markets and — depending on monetary policy responses — contribute to inflation risks and higher interest rates.

Adding to the pressure, the U.S. faces a significant Treasury refinancing task in 2026, with an estimated $9 trillion or more in marketable debt coming due that must be rolled over at today’s higher interest rates — a marked shift from the low rates of the pandemic era. About one‑third of marketable debt is expected to mature in the near term, creating what analysts call a “debt wall.” Meeting this refinancing demand at higher yields could substantially increase interest costs and strain the federal budget.

For the sake of fiscal credibility, economic resilience, and intergenerational fairness, Washington must act — soon. Left unchecked, the debt trajectory points toward a future where borrowing, interest costs, and inflation increasingly shape policy decisions rather than productive investment.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Part of this content was created with formatting and assistance from AI-powered generative tools. The final editorial review and oversight were conducted by humans. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.