Tutorial Categories

Last Updated: January 14, 2026 at 13:30

Mental Accounting: Why We Treat the Same Money Differently - Behavioral Finance Series

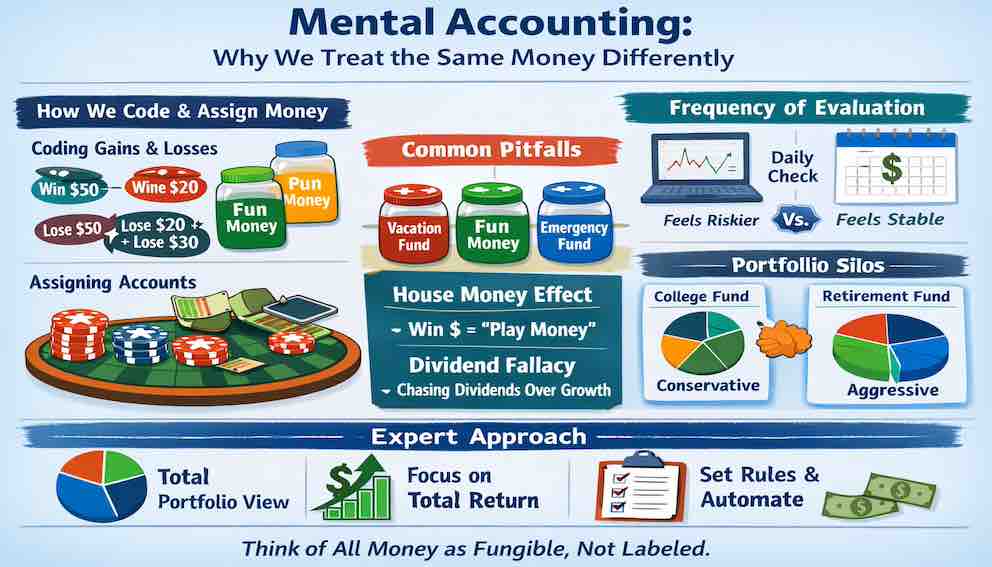

Why do we treat a $1,000 bonus differently from $1,000 of salary? Behavioral finance reveals the answer: mental accounting. Our brains assign money to “accounts” like salary, windfalls, or gifts, applying different rules and emotions to each. This affects how we spend, invest, and take risks—even when all money is financially equivalent. Learn how the house money effect, dividend fallacy, and portfolio silos shape decisions, and discover expert strategies to see your wealth as a whole and make smarter financial choices.

Imagine receiving your monthly salary, carefully budgeting for bills, groceries, and savings. A few days later, you win $200 in a small lottery. Suddenly, you feel free to splurge on a fancy dinner or a new gadget—even though financially, it’s still your money.

Why do we treat this windfall differently from your regular income? This is mental accounting—a behavioral finance concept describing how our minds assign money to different “accounts” and attach different rules to each. Even though all money is fungible(interchangeable), our brains act as if it has labels: “fun money,” “vacation fund,” “bonus,” or “emergency savings.”

Mental accounting shapes spending, investing, and risk-taking decisions, sometimes helping us manage money, but other times leading to inefficient financial behavior.

Core Theory

Behavioral economist Richard Thaler explains mental accounting using a simple but powerful three-part framework. Together, these steps describe how we mentally handle money before we ever make a financial decision.

1. Coding: How We Experience Gains and Losses

The first step is how we mentally “record” gains and losses.

We don’t just look at outcomes objectively—we decide whether to combine them or keep them separate in our minds.

- Small gains feel better when kept separate : Winning ₹500 twice feels more satisfying than winning ₹1,000 once, even though the total is the same. This is called segregation of gains.

- Losses feel less painful when combined : Paying one bill of ₹2,000 hurts less than paying four separate bills of ₹500. This is called integration of losses.

This mental coding shapes how happy or unhappy we feel about financial outcomes—often more than the actual numbers.

2. Assignment: How We Label Money

Next, we assign money to mental “accounts.” This is where labels come in.

Even though all money is identical, we treat it differently based on where it comes from:

- Salary feels “hard-earned” and is protected

- Bonuses, gifts, dividends, or windfalls feel like “extra” money

- A “vacation fund” feels different from a “retirement fund”

Because of these labels, we might:

- Spend a bonus freely

- Invest dividends differently from salary

- Avoid touching certain accounts even when it would be financially sensible

The label, not the logic, often drives the decision.

3. Frequency of Evaluation: How Often We Look

The third and often overlooked part is how frequently we evaluate our accounts.

The same investment can feel very different depending on how often you check it:

- Daily monitoring makes long-term investments feel risky and stressful

- Annual or infrequent review smooths out short-term volatility and reduces emotional reactions

For example, a retirement portfolio evaluated daily may appear volatile and frightening, even if it is well-designed for long-term growth. Evaluated yearly, the same portfolio feels far more stable.

Behavioral Mechanisms at Work

Several psychological forces reinforce mental accounting:

- Source Effect: Money feels different depending on how it was obtained. “Earned” money is guarded carefully; “extra” money (bonuses, rebates, windfalls) is spent or risked more freely.

- Integration vs. Segregation of Gains and Losses: We prefer to separate gains to feel more pleasure and combine losses to reduce pain—often leading to inconsistent financial decisions.

- Fungibility Illusion: In reality, money is fully interchangeable. But mental labels create artificial boundaries, making us treat identical money differently.

Why This Matters in Investing

Mental accounting can quietly distort investment decisions:

- A gain in a “fun money” account may encourage excessive risk-taking

- A “safe” retirement account may be treated too conservatively

- Separate goal-based portfolios may ignore overall risk and return

When money is viewed in isolated buckets instead of as part of a single portfolio, decisions often become emotionally comfortable—but financially inefficient.

Key insight:

Mental accounting feels intuitive and helpful, but without awareness, it can lead investors to take the wrong risks with the wrong money at the wrong time.

Financial Consequences

Individual Investor Pitfalls:

- Risky behavior with windfalls (“House Money” effect): When investors make profits, they often treat those gains as separate from their original money—as if the gains are “extra” or less valuable. This is known as the house money effect. A helpful analogy comes from casinos: Casinos don’t hand you cash; they give you chips. Once your money is converted into chips, losses feel less real, and people are more willing to take risks.

- Dividend Fallacy / Income Mental Accounting: Many retirees prefer dividend-paying stocks partly because they are more risk-averse and value steady cash flows. However, behavioral finance shows that mental accounting also plays a role: dividends are mentally coded as “income” that can be spent comfortably, while capital gains are seen as “principal” that should be preserved. This framing makes dividend income feel safer and more acceptable than selling assets, even when the underlying investment risk is similar. Over time, this preference can lead to higher taxes, reduced diversification, and portfolios that are not optimized for total return.

- Portfolio Silos / Inefficient Asset Allocation: Investors create separate mental or actual accounts for goals like retirement, college, or home purchases. This can lead to overly conservative investments for one goal and overly aggressive investments for another, missing the overall risk-return optimization that comes from viewing all assets together.

- Sunk Cost Traps: Money already “assigned” to a specific account may be avoided for optimal reallocations, reducing overall efficiency.

Market-Level Effects:

- Mental accounting amplifies biases like the disposition effect (selling winners too early, holding losers too long).

- How portfolios are framed (segmented by goal or account) changes investor reactions, influencing market demand and price patterns.

Illustrative Example:

- Retirement account: $10,000

- “Bonus” account: $1,000

Even if invested identically, you may:

- Hold retirement funds during a small loss, avoiding touching “protected” money

- Sell bonus funds after a small gain, chasing immediate reward

This is driven by mental labeling, not rational portfolio optimization.

Expert vs Novice Behavior

Novices:

- Treat money in isolated accounts, reacting emotionally to each category

- Take unnecessary risks with “fun money”

- Fail to see the overall picture, focusing on account-specific gains or losses

Experts:

- Apply holistic mean-variance optimization: All accounts are considered as part of one unified portfolio, maximizing total risk-adjusted return.

- Correctly frame “income”: They avoid the dividend fallacy by focusing on total return and using tax-efficient withdrawals or “virtual dividends.”

- Use rules and automation to override emotional labels (e.g., target allocation, rebalancing)

- Maintain decision journals to track when mental accounting influenced past behavior

Example: A professional advisor might merge bonus, salary, and investment returns in a single portfolio analysis, allocating assets for optimal risk-return rather than letting mental labels dictate strategy.

Practical Mitigation Strategies

- Awareness: Recognize when you’re treating money differently based on source or mental label.

- Holistic Evaluation: Consider all money together when making investment or spending decisions.

- Pre-commitment Strategies: Automate allocation of windfalls into spending, saving, and investing.

- Reframe Gains and Losses: Treat “fun money” gains as part of total wealth to avoid excessive risk-taking.

- Portfolio Consolidation: Review all accounts together for consistent risk management.

- Decision Journals: Track past decisions influenced by mental accounts to learn patterns and improve future behavior.

Nuance & Debate

- Adaptive Uses: Mental accounts help in budgeting and self-control. Labeling money (e.g., “rent,” “vacation”) can prevent impulsive spending.

- Where it becomes harmful: Problems arise when mental accounting bleeds into investing, leading to inefficient allocation and unnecessary risk.

- The “Pain of Paying”: How we perceive money spent influences mental accounting. Cash feels more “real” than credit card or subscription payments, affecting spending behavior.

- Interaction with Other Biases: Mental accounting often amplifies loss aversion, FOMO, and the disposition effect.

- Cultural and Temporal Variation: Attitudes toward gifts, windfalls, or bonuses influence how mental accounts are formed and used.

Clear Takeaway

Mental accounting shows that we treat money differently depending on its mental label, even though all money is fungible. Awareness of this tendency helps investors:

- Make decisions based on total wealth rather than individual accounts

- Reduce unnecessary risk from “house money” thinking

- Avoid the dividend fallacy and portfolio silos

- Use mental accounts as budgeting tools without harming investment efficiency

Reflective Prompt:

Next time you receive a bonus, dividend, or gift, ask yourself:

“Am I treating this money differently than my other assets? Would I make the same choice if all my money were viewed together?”

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.