Last Updated: February 10, 2026 at 19:30

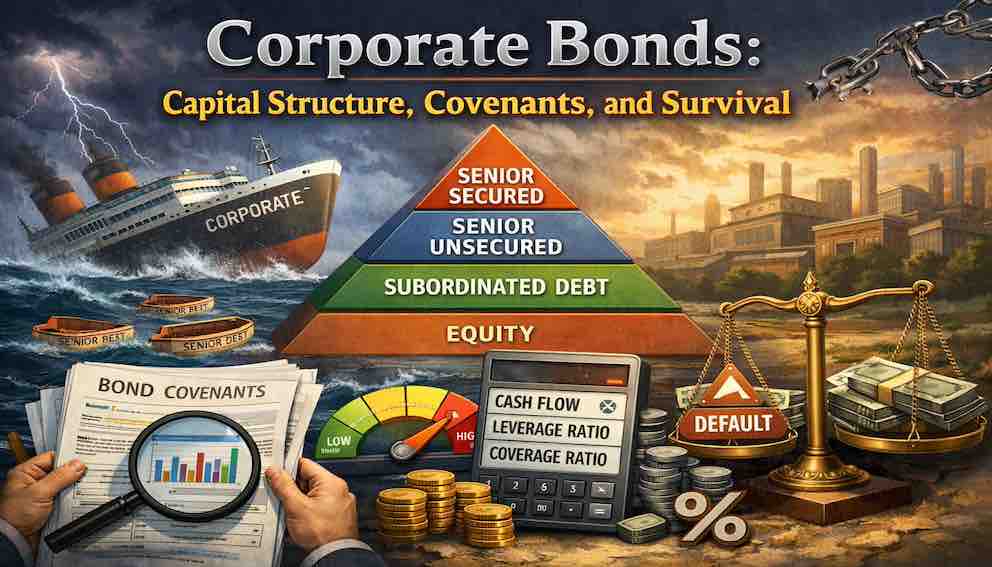

Corporate Bonds: Capital Structure, Covenants, and Survival

Corporate bonds are a vital part of fixed income investing, but they behave very differently from government bonds because they reflect the unique realities of each company. This tutorial explores the structure of corporate debt, the role of covenants in protecting bondholders, and the critical distinction between senior and subordinated bonds. You will learn how to evaluate default risk versus dilution risk, understand coverage ratios and cash flow metrics, and appreciate why, for bondholders, a company’s survival matters infinitely more than its spectacular success. Through clear examples and practical mental models, we’ll show how to navigate the corporate bond world not with hope, but with a disciplined, defensive view of your legal rights and financial protections.

Introduction: From Sovereign Promises to Corporate Realities

We've spent time in the realm of government bonds, where the primary risks are macroeconomic—shifting yield curves, changing interest rates, and the silent erosion of purchasing power due to inflation. Now, we step into a more intimate, and often more complex, arena: the world of corporate bonds. Here, the promise of repayment isn’t backed by the taxing power of a nation, but by the cash flows, assets, and management decisions of a single company. This shift transforms the lens through which you must evaluate risk.

The mental model you must carry is simple but crucial: bondholders care about survival, not success. Unlike shareholders, who thrive when a company grows spectacularly, bondholders’ primary concern is whether the company can continue to generate enough cash to pay interest and principal on time. Every decision—how you read covenants, assess capital structure, or calculate risk—flows from this core principle.

Part 1: The Capital Structure – Your Legal Place in Line

Think of a company as a large, valuable ship. That ship did not appear by magic—it was paid for by two very different groups of people. One group is the shareholders. They are the owners of the ship, and they hope that, by operating it well, they can sell its cargo at a profit. The other group is the lenders, or bondholders. They provided money to help build and equip the ship, and in return they expect something much more modest and predictable: regular interest payments and, eventually, their money back.

Now imagine that the ship runs into a severe storm and begins to take on water. At that moment, optimism and future plans no longer matter. What matters is how the remaining value of the ship is saved and divided. This process is not random and it is not based on who tells the best story. It follows a strict legal order called the capital structure.

The capital structure is simply the rulebook that determines who gets paid first, who gets paid later, and who may not get paid at all when things go wrong. Your bond’s position within this structure is not flexible and it is not open to negotiation in a crisis. It is written into the legal contracts from the beginning. That position alone can decide whether you recover all of your money, only part of it, or nothing whatsoever.

Senior Secured Debt: First to the Lifeboats

At the very top of the hierarchy are senior secured lenders. They hold not just a promise, but a legal claim (a “lien”) on specific assets of the company—factories, patents, or real estate. In our sinking ship analogy, they financed the lifeboats themselves and have the legal right to them. If the company fails, these assets are sold, and these lenders are paid first from the proceeds. Because of this security, senior secured debt generally carries the lowest yield among corporate bonds.

Senior Unsecured Debt: A General Promise, but Still Near the Front

Next in line are senior unsecured bonds. They have a general claim on the company’s assets but do not hold collateral. They still stand ahead of subordinated debt and equity, akin to passengers with priority boarding passes for the lifeboats. While safer than subordinated debt, they are riskier than secured debt and therefore offer slightly higher yields.

Subordinated (Junior) Debt: Last in Line

Below these are subordinated or junior bonds, whose legal agreements explicitly state they are paid only after all senior claims are satisfied. In a distress scenario, these bondholders often receive little or nothing. The higher yields offered by these bonds compensate investors for their precarious position—hazard pay for taking additional risk.

Equity: The Owners of the Ship

At the bottom of the hierarchy are shareholders. They own whatever remains after all debts are repaid. In a sinking ship, they are the last to get a lifeboat, and often there is nothing left. While equity investors enjoy upside when the company thrives, they bear the brunt of losses first.

A Concrete, Sobering Example: The Retail Bankruptcy

Consider a large national retailer overwhelmed by debt and competition, which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy:

- $1 Billion in Senior Secured Debt (backed by inventory and distribution centers)

- $500 Million in Senior Unsecured Bonds

- $300 Million in Subordinated Bonds

The company’s assets were liquidated for $1.2 billion. The secured lenders were paid in full first, taking $1 billion. The remaining $200 million went to senior unsecured bondholders, who received only 40 cents on the dollar. Subordinated bondholders and shareholders received nothing. This is not an anomaly; it is the capital structure in action. Even the seemingly “high-yield” subordinated bond turned into a total loss because of legal priority.

Part 2: Covenants – The Rulebook That Protects You

If the capital structure tells you your place in line during a fire, covenants are the fire alarms, sprinklers, and safety codes designed to prevent the fire from starting in the first place. Covenants are legally binding clauses in the bond's contract (the “indenture”) that restrict the company’s actions to protect your capital.

Think of covenants not as red tape, but as your remote-control tools as a lender. You can’t run the company, but you can establish rules for how it is run.

Incurrence Covenants: The “Checkpoint” Rules

These rules do not prohibit an action outright but say, “You can only do this if you pass a financial test first.” For example:

"The company cannot pay a dividend unless its leverage ratio (Debt/EBITDA) is below 4x."

This prevents management from siphoning cash to owners while overburdening the company with debt that threatens bondholders.

Maintenance Covenants: The “Constant Health” Rules

These covenants require the company to maintain certain financial thresholds at all times, often tested quarterly. A classic example is the interest coverage ratio:

"The company must maintain EBIT to Interest Expense of at least 3.0."

Breach of this covenant is considered an immediate default, giving bondholders the right to demand repayment or renegotiate terms. These covenants act as early-warning systems and levers of control.

Why “Covenant-Lite” Is a Warning Sign

Many recent bonds, particularly in leveraged buyouts or private credit, have very weak or minimal covenants (“cov-lite”). Purchasing these bonds is like buying a car without airbags or brakes. Yield may be slightly higher, but you voluntarily give up essential protections, significantly altering your risk profile.

Part 3: Default Risk vs Dilution Risk – Who Worries About What

Bondholders must distinguish default risk from dilution risk:

- Default Risk is the probability that a company fails to make interest or principal payments. This is the primary risk for bondholders.

- Dilution Risk occurs when a company issues new equity, diluting existing shareholders’ ownership. Bondholders are generally unaffected by dilution unless new equity issuance alters their legal claims.

Example:

A company struggles to make interest payments. Bondholders worry about whether cash flow will cover obligations (default risk). Shareholders worry about issuance of new shares, which could dilute their ownership and reduce the value of their stake (dilution risk).

Mental Model: Bondholders are like insurers—they care if the house burns down, not if the house could have been worth more. Shareholders are speculators—they care about the potential upside but bear the risk if the company fails.

Part 4: Cash Flow, Leverage, and Coverage – The Bondholder’s Compass

For corporate bond investors, cash flow matters more than reported profit, and simple financial ratios act like navigation instruments that help you judge whether a company can keep paying its debts. The goal is not to predict greatness, but to understand whether the company has enough financial breathing room to survive ordinary stress.

Cash Flow vs Accounting Profit

A company can appear healthy on paper and still struggle to pay its bondholders. This happens because accounting profit and actual cash are not the same thing.

Imagine a company that reports $50 million in net income for the year. At first glance, this sounds reassuring. However, suppose that during the same year the company spent $40 million opening new stores, upgrading factories, or maintaining essential equipment. That money has already left the business. After these necessary expenses, only $10 million of real cash remains.

That remaining $10 million is what must be used to pay interest on bonds, repay debt, and handle unexpected problems. This leftover amount is called free cash flow. It represents the actual pool of money from which bondholders are paid. No matter how impressive the profit figures look, interest payments can only be made with cash that truly exists.

Mental model: accounting profit reflects how the business is measured on paper, but cash reflects what the business can actually spend. Profit can be debated and adjusted; cash cannot. For bondholders, cash is what keeps the lights on and the interest checks arriving.

Leverage and Coverage Ratios

Once you understand cash flow, financial ratios help you judge how stretched a company really is.

A leverage ratio compares the company’s total debt to its earnings or assets. This tells you how much debt the company is carrying relative to its size. A helpful way to think about leverage is as weight on the ship. The more debt a company has, the heavier it becomes. A heavily loaded ship can still move forward in calm seas, but it becomes far more vulnerable when the weather turns.

An interest coverage ratio looks at how easily a company can pay its interest bills. It compares earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) to the company’s annual interest expense. This ratio measures stamina—how comfortably the company can keep meeting its obligations.

Here is a simple example. Suppose a company earns $100 million a year before interest and taxes, and its annual interest payments are $20 million. This produces an interest coverage ratio of 5. That means the company earns five times more than it needs to cover interest payments, which suggests a comfortable margin of safety.

Now imagine earnings fall to $30 million while interest payments remain the same. Coverage drops to 1.5. At that point, the company has very little room for error. A small downturn, a rise in costs, or a temporary disruption could make it impossible to pay interest without borrowing more or selling assets. For bondholders, this is a clear warning sign.

Together, cash flow, leverage, and coverage ratios tell a simple story. They show whether a company is lightly loaded and resilient, or heavily burdened and fragile. Bond investing is not about hoping conditions remain perfect. It is about understanding how much stress a company can absorb before something breaks.

Part 5: Yield, Credit Spread, and Compensation for Risk

Corporate bonds typically offer higher yields than government bonds. This yield premium compensates investors for taking on extra risk, such as default potential, subordinated status, or weak covenants.

Example:

- Government bond yield: 4%

- Similar-maturity corporate bond yield: 6%

The 2% difference—the credit spread—is the market pricing of extra doubt: it reflects uncertainty about repayment, company-specific risk, and economic cycles.

Mental Model: Extra yield prices extra doubt. High yield is tempting, but it signals that risk is correspondingly higher. Assess whether the reward justifies the hazard.

Part 6: The Bondholder’s Toolkit – Asking the Right Questions

With these mental models in place, investors should focus on defense over speculation:

Analyze Capital Structure

- How much debt exists ahead of your bond?

- What claims are secured versus unsecured?

- Are subordinated bonds likely to get wiped out in distress?

Examine Covenants

- Debt incurrence tests: limits on new borrowing

- Restricted payments: limits on dividends or buybacks

- Asset sale sweeps: mandatory debt repayment from asset sales

Focus on Free Cash Flow

- Track operational cash after essential reinvestments

- Ensure it is sufficient to cover interest and principal

Consider Leverage and Coverage Ratios

- Debt/EBITDA, Debt/Assets, EBIT/Interest Expense

- Interpret using mental models: weight and stamina

Assess Yield vs Risk

- Compare the bond’s yield to the credit spread

- Ask: does this extra return fairly compensate for default, subordinated status, or weak covenants?

Conclusion: The Philosophy of the Prudent Lender

Navigating corporate bonds is an exercise in disciplined, defensive thinking. We have learned that:

- Your legal priority in the capital structure matters more than the company’s story or brand. In distress, the line is unforgiving.

- Covenants are your safeguards. They allow you to constrain risky behavior without owning the company.

- Default risk is your primary concern; dilution risk belongs to shareholders.

- Cash flow, leverage, and coverage ratios are your compass. Profit is only an opinion; cash is fact.

- Credit spreads reflect compensation for risk. Extra yield prices extra doubt.

The ultimate mental model: you are not buying a company; you are underwriting an insurance policy against default. The premium you receive—the yield—must be proportionate to the risk you are assuming. By thinking like a cautious, contractual lender, you separate yourself from equity dreamers and build a fixed-income portfolio grounded in legal rights, financial reality, and prudent protection, not mere hope.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.