Last Updated: February 8, 2026 at 16:30

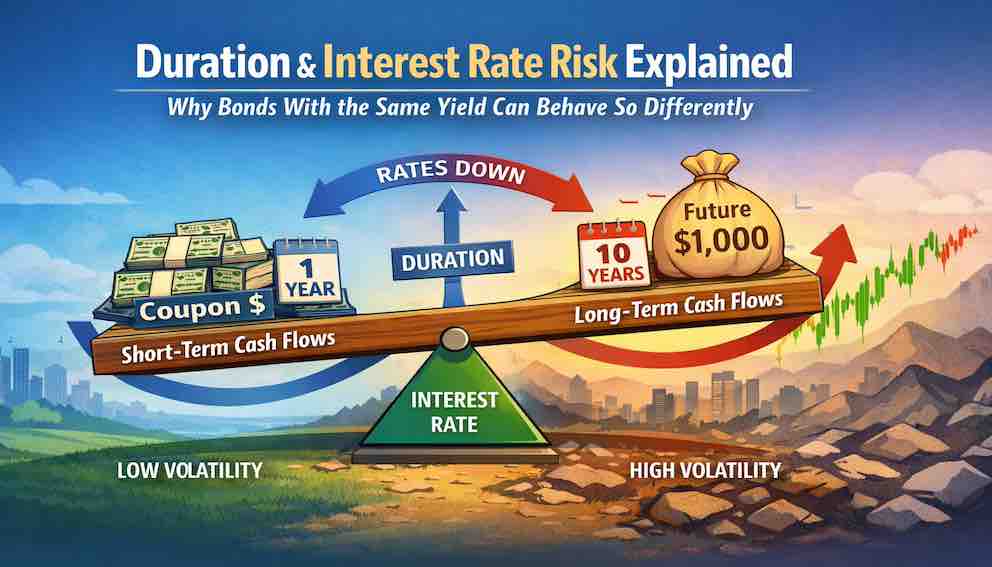

Duration and Interest Rate Risk Explained: Why Bonds With the Same Yield Can Behave So Differently

Yield tells you how much return a bond is expected to deliver. Duration tells you how violently that return can move when interest rates change. Duration is a way to measure how sensitive a bond’s price is to interest rate changes, without needing heavy maths. In this tutorial, you’ll see why two bonds with the same yield can have very different price swings, how duration is a “time‑weighted average” of when you get your money back, and how you can use it as a practical dial to control risk.

Introduction: When Yield Doesn’t Explain the Rollercoaster

In the previous tutorial, you learned that Yield to Maturity (YTM) is a powerful comparison tool. It compresses income (coupons) and price change (discount or premium) into a single annual return number, assuming you hold to maturity and reinvest coupons at the same rate.

Now consider two 10‑year bonds from the same issuer, both with a YTM of 5%:

“Steady Eddy”

- Maturity: 10 years

- Coupon: 7% (70 per year)

- Price: 1,150 (premium)

“Long Haul Larry”

- Maturity: 10 years

- Coupon: 3% (30 per year)

- Price: 850 (discount)

YTM tells you they both offer the same expected annual return if held to maturity under standard assumptions. But if interest rates rise by 1% tomorrow, the low‑coupon bond’s price (Long Haul Larry) will fall more than the high‑coupon bond’s price (Steady Eddy)—typically by about 9% versus 7%, because Larry’s duration is longer. Same yield, different pain.

Yield equalises expected return under stable conditions. It hides how fragile each bond is to rate changes. Duration is the missing concept that reveals that fragility. Duration is not the same as maturity and it will be explained shortly.

Part 1: Time as a Risk Amplifier

Core idea: The farther away a payment is, the more its value today changes when interest rates move.

Here's why:

- A payment due next year: Small effect from rate changes.

- A payment due in 30 years: Big effect from the same rate change.

A bond = coupons + final principal.

Duration = average time until you get all your money back (weighted by payment size).

Simple rule:

More money in distant payments → higher duration → more price sensitivity.

High coupon bonds get more cash back early → shorter duration → less price sensitivity.

Low coupon bonds have most value at the end → longer duration → more price sensitivity.

Price risk vs. reinvestment risk

High coupons = less price risk (shorter duration), but more reinvestment risk (lots of cash to reinvest).

Duration measures price sensitivity only.

Part 2: Duration vs. Maturity – Journey vs. Deadline

Maturity is the date the bond ends and the final principal is repaid.

Duration is the average time it takes to get your money back, taking into account all payments and how large they are.

Revisit our two 10‑year bonds:

Steady Eddy (7% coupon)

- You receive 70 every year.

- A big chunk of your original investment is returned steadily through coupons.

- Only some of your value is concentrated in the final principal payment.

- Typical duration: somewhere around 7½ years (shorter than 10).

Long Haul Larry (3% coupon)

- You receive just 30 each year.

- Most of your value is tied up in the final principal and price gain (from 850 to 1,000).

- A large share of the total payoff is far in the future.

- Typical duration: around 9 years (closer to full maturity).

This leads to a simple rule:

- The lower the coupon, the closer the duration is to the maturity.

- A zero‑coupon bond has duration equal to its maturity (you get everything at the end).

- The higher the coupon, the shorter the duration relative to maturity (more value comes back earlier).

So:

- Maturity tells you when the story ends.

- Duration tells you how spread out the story is and how sensitive that story is to interest rate changes.

Part 3: Duration as a Price Sensitivity Meter

Duration becomes truly useful when you see how it links changes in interest rates to changes in price.

For small rate moves, Modified Duration gives a rule of thumb:

Approx. Percentage Price Change ≈ −Duration × Change in Yield

- The minus sign shows the inverse relationship: when yields go up, prices go down.

Using our approximate durations:

- Steady Eddy: Duration ≈ 7.5

- Long Haul Larry: Duration ≈ 9.0

If yields rise by 1 percentage point (0.01):

- Steady Eddy: price change ≈ −7.5 × 1% = −7.5%

- Long Haul Larry: price change ≈ −9.0 × 1% = −9.0%

If yields fall by 1 percentage point:

- Steady Eddy: price change ≈ +7.5%

- Long Haul Larry: price change ≈ +9.0%

So even though both bonds had a 5% YTM:

- Larry is more volatile: bigger losses when rates rise, bigger gains when rates fall.

- Eddy is less volatile: smaller swings in both directions.

Foreshadowing convexity

Duration is a linear approximation. For larger interest rate moves, bond prices curve rather than move in straight lines. This curvature—called convexity—explains why price gains from falling rates often exceed losses from rising rates. We’ll explore convexity in a future tutorial.

Part 4: Duration as a Personal Risk Dial

Duration is not something that just “happens” to you; it’s a choice you make when you pick bonds or bond funds. It’s the main dial you use to set how much interest rate risk you’re taking.

Think of duration in bands:

High duration (e.g., 8–15+ years)

- Large price moves when rates change.

- More potential upside if rates fall.

- More potential downside if rates rise.

- Suitable only if you have a long horizon and can tolerate big swings.

Low duration (e.g., 1–3 years)

- Small price moves when rates change.

- Less upside from falling rates, but less pain from rising rates.

- Often used for near‑term goals or by investors who prioritise stability.

One classic misunderstanding:

“Government bonds are always safe.”

Long‑term government bonds (like 20‑ or 30‑year Treasuries) usually have very low credit risk—you are likely to be repaid. But their duration is high, so their prices can swing a lot when interest rates move. They are “safe” in terms of default, but not “safe” in terms of short‑term price stability.

Duration helps you separate these two ideas: credit safety vs. interest rate risk.

Part 5: Putting Duration to Work

Once you understand duration, you can use it in multiple practical ways.

1. Reading bond funds correctly

When you look at a bond fund or ETF:

- Yield tells you the expected return (under assumptions).

- Average duration tells you how much its price will move when rates change.

A “long‑term Treasury ETF” with a duration of, say, 17 years is not a slow, savings‑account‑like product. A 1% move in yields can mean roughly a 17% move in price in the short term. Duration explains why some “conservative” funds behaved like high‑beta equities when rates jumped.

2. Matching investments to your time horizon

If you need your money back in about 2 years for a specific goal (house deposit, tuition):

- Focusing on bonds or funds with duration around 2 years or less reduces the risk that a rate spike will significantly erode your capital right before you need it.

- The closer the duration is to your horizon, the less interest rate risk you face at that horizon.

3. Expressing a view on interest rates

If you have a view on rates:

- Expecting rates to fall → you might increase duration to benefit more from price gains.

- Expecting rates to rise, or if you are unsure and want to protect capital → you might shorten duration to limit price losses.

Duration lets you turn a macro view (“I think rates will do X”) into a concrete portfolio choice (“I will hold bonds with duration Y”).

Conclusion: Yield and Duration – Return and Risk Together

You now have the two key lenses for understanding bonds and bond funds:

- Yield is the reward lens: it summarises the expected return if things go according to plan.

- Duration is the interest rate risk lens: it tells you how sensitive that expected return is to changes in yields.

Yield answers:

“What am I being paid (on paper) if I hold this bond under standard assumptions?”

Duration answers:

“How much can the price move if rates change while I’m holding it?”

A high‑yield, long‑duration bond isn’t automatically “better” than a low‑yield, short‑duration bond. It’s simply riskier in terms of price volatility and more dependent on your ability to hold through rate cycles.

Two bonds can have the same yield and yet represent very different journeys: different cash‑flow timing, different reinvestment risk, and very different reactions to rate moves. Duration helps you choose the journey you can actually stick with, not just the yield that looks best on a fact sheet.

In the next tutorial, we’ll turn to the other major dimension of bond risk that duration does not measure: Credit Risk—the possibility that the issuer won’t pay you back in full and on time.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.