Last Updated: January 29, 2026 at 10:30

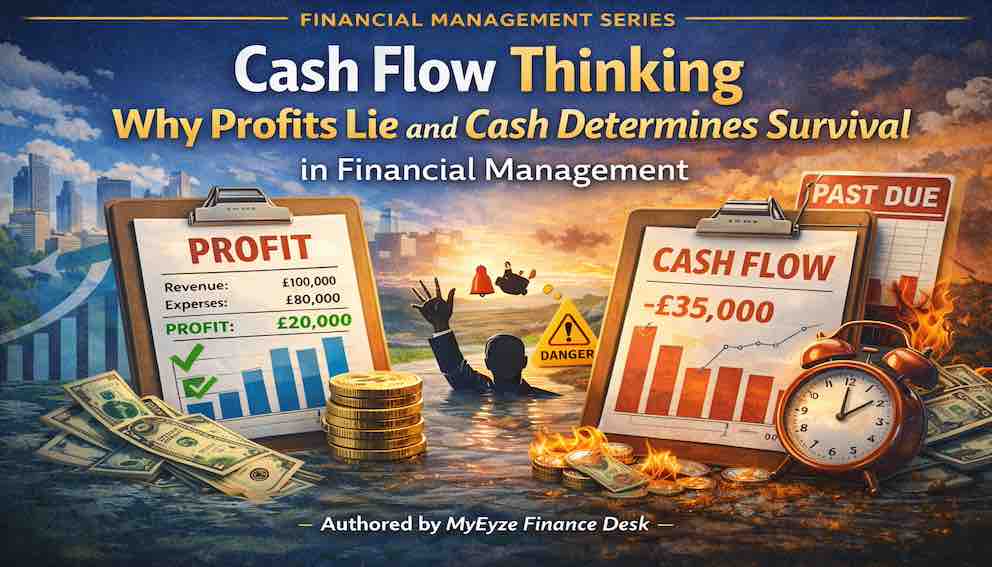

Cash Flow Thinking: Why Profits Lie and Cash Determines Survival in Financial Management - Financial Management Series

Many businesses fail not because they are unprofitable, but because they run out of cash at the wrong moment. This tutorial explains why accounting profits can look healthy even as financial stress quietly builds underneath. By starting with everyday timing mismatches and moving into real business examples, it shows how revenue, profit, and cash flow answer very different questions. Readers will learn why cash flow statements exist, how to read them with confidence, and why financial managers must think in terms of liquidity, timing, and survival rather than reported earnings alone.

Cash Flow Thinking: Why Profits Lie and Cash Determines Survival in Financial Management

In our previous tutorial, we spent a long time sitting with a simple but unsettling idea: money changes its meaning when time is introduced. A pound today is not interchangeable with a pound tomorrow, because between now and then, opportunity, uncertainty, obligation, and inflation all quietly do their work. Once that intuition is accepted, a second realization follows almost automatically, even if it is not always stated clearly.

If time reshapes the value of money, then any system that records money without respecting timing will inevitably distort reality.

Accounting profit is such a system. It is useful, structured, and standardized, but it is also shaped by conventions about when things are counted rather than when cash actually moves. Cash flow, by contrast, sits directly at the intersection of time, uncertainty, and obligation. It is not elegant, and it is not abstract, but it determines whether an individual, a business, or an institution survives the next month.

To see why this matters, it helps to begin somewhere familiar, long before we talk about companies or financial statements.

Everyday Intuition: Income, Bills, and Bad Timing

Imagine an individual who earns a good salary on paper. Their employment contract shows a solid annual income, and if you looked only at that number, you would conclude that they are financially healthy. Now imagine that their rent is due on the first of every month, their credit card bill closes on the 25th, and their paycheck arrives on the 30th.

On paper, nothing is wrong. Over the course of a year, income comfortably exceeds expenses. But in the space between the first and the 30th, cash can run dangerously thin. Rent does not accept explanations about future income. Credit card companies do not pause interest because money is “on the way.” The problem here is not profitability in the annual sense; it is timing.

Most people recognize this instinctively. This is why people with decent incomes still worry about emergency funds, overdrafts, and short-term liquidity. They know, often without articulating it, that survival is governed by when money arrives, not just by how much arrives in total.

This same intuition applies to businesses, but the mechanisms that obscure it are more complex and more formalized.

Revenue, Profit, and Cash: Three Different Questions

Before we move further, it is important to slow down and separate three ideas that are often treated as interchangeable in casual conversation: revenue, profit, and cash flow. They sound similar, but they answer fundamentally different questions.

- Revenue asks: How much value did we deliver, measured by sales, during this period?

- Profit asks: After matching revenues with their associated costs, how much value did we create according to accounting rules?

- Cash Flow asks: How much actual money moved into or out of the bank during this period, and when did it move?

None of these questions is wrong. Each exists because it captures something the others cannot. The problem begins when profit is treated as a proxy for cash, or when revenue growth is mistaken for financial health.

To understand why this confusion is so persistent, we need to look at how profit is constructed.

Profit as an Accounting Construct Shaped by Time

Profit is not a lie in the sense of being deliberately false. It is a structured summary built on assumptions about timing. Accrual accounting, which governs how profit is calculated, tries to answer a reasonable question: What economic activity belongs to this period, regardless of when cash happens to move?

If a business delivers a product in March but is paid in May, accounting logic says that the revenue belongs to March, because that is when the value was created. Similarly, if a company buys a machine that will be used for ten years, accounting does not treat the full cash outflow as a cost in year one. Instead, it spreads the expense over time through depreciation.

These choices make profit more stable and more comparable across periods. They help investors and managers see patterns rather than noise. But they also introduce time distortions that can hide stress.

Profit smooths reality. Cash exposes it.

How Profit Can Exist Without Cash: A Step-by-Step Business Example

Consider a growing manufacturing business that sells equipment to other companies. To win customers, it offers generous payment terms: delivery today, payment in ninety days. Orders increase rapidly. Revenue rises. Profit, calculated by matching revenues with production costs, looks healthy.

But now follow the cash.

To produce the equipment, the business must buy raw materials immediately. It must pay workers every month. It must pay rent, utilities, and suppliers long before customers send their money. As sales grow, these upfront cash demands grow as well. The faster the business grows, the more cash it needs just to keep operating.

On the income statement, this looks like success. On the bank statement, it feels like suffocation.

This is not a hypothetical edge case. It is one of the most common causes of failure among growing firms. The business is not unprofitable. It is not poorly managed in a technical sense. It simply commits cash today in exchange for cash tomorrow, and tomorrow arrives too late.

Here is where the time pillar reasserts itself. Future cash, no matter how certain it appears, cannot pay today’s bills.

To see this divergence in its simplest form, let's look at a single transaction:

Imagine a consulting firm completes a £10,000 project in December. It invoices the client immediately, but the payment terms are 60 days.

- The Income Statement for December will show: Revenue: £10,000, Profit: (let's say) £6,000. It looks like a great month.

- The Bank Statement for December will show: Cash Inflow: £0.

- The firm was profitable but received no cash. It must still pay salaries, rent, and taxes in December using cash it already had. This gap between earning profit and receiving cash is the daily reality of business.

Inventory, Receivables, and the Silent Drain on Cash

The same logic appears in other forms. A retailer that stocks more inventory in anticipation of higher demand shows confidence and growth potential. But inventory is cash that has been transformed into boxes on shelves. Until those boxes are sold and paid for, they cannot fund payroll.

Similarly, accounts receivable represent money that customers owe. On paper, this is an asset. In reality, it is a promise tied to someone else’s timing, priorities, and solvency. A customer’s delay becomes the firm’s liquidity problem.

None of this appears alarming if one looks only at profit. All of it becomes obvious when one looks at cash movement over time.

Obligations Do Not Respect Accounting Elegance

There is another reason cash flow deserves priority: obligations are real, specific, and time-bound. Loan repayments have due dates. Wages must be paid on schedule. Taxes do not accept explanations about accruals.

Accounting profit can say that a company had a good quarter. The bank, the payroll system, and the tax authority care only about whether cash is available now.

This is why cash flow is the point where time, uncertainty, and commitment collide. It is where future expectations are tested against present reality.

Why the Cash Flow Statement Had to Exist

Once these problems are felt, the existence of the cash flow statement stops feeling like an accounting curiosity and starts feeling inevitable. The income statement tells a story about performance. The balance sheet shows a snapshot of resources and obligations. But neither answers the most urgent operational question: How did cash actually move?

The cash flow statement exists to answer that question directly.

It strips away accrual assumptions and focuses on what entered and left the business during a period. It typically separates cash movements into three categories, which mirror how a business lives:

- Operating Activities: Cash from selling goods/services and paying for day-to-day expenses. This shows whether the core business generates or consumes cash.

- Investing Activities: Cash used for buying or selling long-term assets like equipment or property.

- Financing Activities: Cash from raising money (loans, issuing shares) or paying it out (dividends, loan repayments).

When read carefully, this statement reveals whether profits are being converted into cash, delayed into promises, or offset by hidden demands.

Seeing Failure Before It Happens

A firm moving toward failure often leaves clear traces in its cash flow long before profits collapse. Operating cash flow weakens even as reported earnings remain strong. Short-term borrowing increases to cover routine expenses. Inventory and receivables swell faster than sales.

To a financial manager trained to think in cash terms, these are not abstract warnings. They are signals that time is working against the firm.

This perspective changes how decisions are evaluated. Growth is no longer automatically good. Long payment terms are no longer just a sales tactic. Profit margins are no longer sufficient indicators of health.

Liquidity becomes a strategic variable, not a residual outcome.

Cash-First Thinking as Financial Management

At this point, the deeper lesson should be clear. Financial management does not reject profit, but it refuses to worship it. It recognizes profit as a useful abstraction that must always be checked against cash reality.

A financial manager asks questions such as: When will this cash arrive? What commitments must be honored before then? How sensitive is survival to small delays or shocks? These questions are not pessimistic. They are practical responses to a world shaped by time and uncertainty.

This mindset does not eliminate risk, but it prevents a particular kind of blindness: the belief that reported success guarantees survival.

Conclusion: What We Have Learned

In this tutorial, we extended the Time pillar into one of its most concrete consequences. We saw that revenue, profit, and cash flow answer different questions, and that confusing them can be fatal. We explored how accounting profit, shaped by accrual conventions, can look healthy even as cash drains away. Through everyday intuition, business examples, and a simple numerical illustration, we saw why firms fail not because they lack profitability, but because cash arrives too late or leaves too early.

We also saw why the cash flow statement exists, and why it deserves careful attention from anyone responsible for financial decisions. Cash flow is where time becomes unavoidable, where promises meet obligations, and where survival is decided.

As we continue the series, this cash-first perspective will remain essential. Because once time and cash are understood, risk and human behavior can no longer be treated as abstract ideas. They become forces that act on real money, in real moments, with real consequences.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.