Last Updated: February 2, 2026 at 10:30

The Herd Instinct in Investing: Why Following the Crowd Feels Safe But Is Often Costly - Investing Wisdom

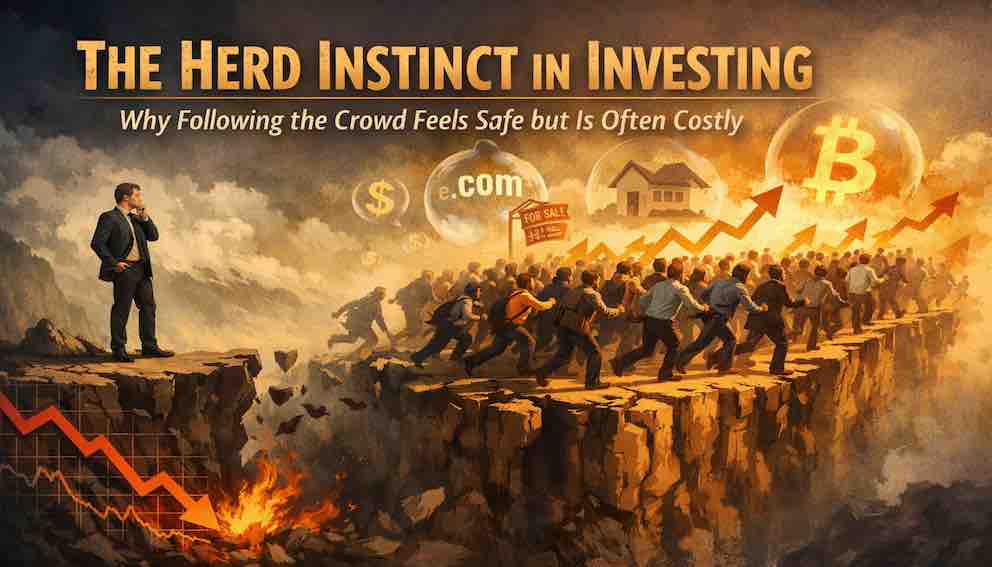

The urge to follow the crowd is a natural human instinct. In modern markets, it can often lead to big mistakes. This tutorial looks at why we trust consensus, from classic psychology experiments to real-world market manias. Using examples from the Dotcom bubble, the 2008 housing crisis, and cryptocurrency surges, we show how herd behavior repeats in predictable ways. Most importantly, we provide practical ways to recognize this instinct and develop habits that help you think independently and make better financial decisions.

The Herd Instinct: When Safety in Numbers Becomes Danger to Wealth

A Simple Experiment That Explains Everything

In the 1950s, psychologist Solomon Asch gathered groups of eight people in a room. Only one was the true subject; the others were actors. They were shown a simple test: match the length of a line on one card to one of three lines on another.

For the first few rounds, everyone gave the obvious, correct answer. Then, the actors began unanimously choosing a line that was clearly wrong. Faced with this unanimous but incorrect consensus, the real subject had a choice: trust their own eyes or agree with the group.

Approximately 75% of subjects conformed to the group’s incorrect answer at least once. Some did so while visibly uncomfortable, doubting their own perception. Others internalized the error, convincing themselves the group must be right.

Asch’s experiment did not involve money, status, or fear. It involved only lines on a card and the pressure of seven strangers. Yet it revealed a profound truth: the human need to belong can override the evidence of our own senses. This is the purest form of the herd instinct—and it is the unseen current beneath every market mania and panic.

From the Laboratory to the Trading Floor

In investing, the stakes are immeasurably higher, but the mechanism is identical. The “lines” are replaced by valuation metrics, business models, and risk assessments. The “group” is the chorus of financial media, analyst upgrades, and the visible success of peers.

The instinct to follow is not a sign of foolishness. It is a legacy of our evolution. For our ancestors, separation from the tribe meant predation, exposure, and death. Consensus equaled survival. The neural pathways that flood us with anxiety when we stand alone—and with comfort when we fall in line—are ancient and powerful. In the marketplace, this ancient alarm system is triggered not by the rustle of a predator, but by the fear of missing out while others prosper, or the terror of losing alone while others have already fled.

This explains why doing the rational thing in markets often feels irrational. Buying when there is “blood in the streets” (as the old adage goes) feels terrifying because the herd is selling in panic. Selling an asset that has become ludicrously overvalued feels risky because the herd is still buying with euphoria. The emotional cost of going against the group feels immediate and visceral; the financial cost of following them is often abstract and delayed.

A Brief History of Crowded Rooms: Dotcoms, Houses, and Digital Tokens

To see the herd instinct in its full destructive splendor, we must look at specific moments where consensus divorced itself from reality.

1. The Dotcom Bubble: The Story of theglobe.com

In November 1998, a small social networking startup called theglobe.com went public. Its business model was unproven, its losses were mounting, but it was riding the wave of “internet” hype. On its first day of trading, the stock price soared from an IPO price of $9 to close at $63.50—a 606% gain, then a record. Employees celebrated on the trading floor; headlines proclaimed a new era. The company’s market valuation momentarily eclipsed that of established giants. Here, social proof was absolute: the market price itself became the reason to buy. The logic was circular: “It’s going up because people are buying it, and people are buying it because it’s going up.” theglobe.com never turned a profit. It was delisted within a few years, and the stock became worthless. The early gains were real only for those who sold before the narrative cracked.

2. The 2008 Housing Mania: The Miami Condo Flip

In the mid-2000s, a cultural script took hold in parts of the U.S.: real estate only goes up. In Miami, a speculative frenzy saw condominiums bought and sold like tickets to a concert—often before the building was even completed. The consensus was reinforced at every turn: easy credit from banks, breathless television shows about “flipping,” and neighbors boasting about their effortless equity. The safety of consensus was an illusion built on collective amnesia about the very possibility of decline. When credit tightened, the game of musical chairs ended. The condos that were “sure things” became anchors of debt. The herd had collectively forgotten that prices could fall.

3. The Cryptocurrency Cycles: The Fear of Being Left Behind

Cryptocurrency surges offer a modern, digital-age template of the same instinct. When prices rise exponentially, a new consensus forms: “This is the future of finance; old rules don’t apply.” The social proof is digital but no less potent—displayed in portfolio screenshots on social media, celebrity endorsements, and the gnawing anxiety that a technological revolution is passing you by. The asset’s extreme volatility is reinterpreted not as risk, but as proof of its transformative power. Each cycle draws in a new herd, convinced this time is different, only to be reminded that gravity—whether financial or psychological—still exists.

The Anatomy of a Herd Movement

These disparate events share a common emotional anatomy:

- Stage 1: The Rational Foundation. A genuine innovation or opportunity emerges (the internet, affordable credit, blockchain).

- Stage 2: The Early Gain. Astute or lucky participants profit, drawing attention.

- Stage 3: The Narrative Hardens. A simple, compelling story takes hold (“The old economy is dead,” “Housing is a can’t-lose investment”). The media amplifies it.

- Stage 4: Social Proof Becomes the Primary Driver. People stop analyzing the asset and start analyzing the behavior of other people. Participation becomes a social imperative.

- Stage 5: The Euphoric Peak. The last skeptical holdouts capitulate and buy in, exhausted by the psychological cost of standing apart. This often marks the top.

- Stage 6: The Fracture & Panic. When the narrative cracks, the herd reverses direction. The safety of consensus instantly becomes the danger of the stampede.

Resisting the Pull: Building Habits of Mind

Knowing the pattern is not enough. We must build mental habits that act as counter-weights to our instinctual pull toward the herd. This is not about becoming a stubborn contrarian, but about cultivating intellectual independence.

1. Interrogate the Narrative, Not the Price.

When an idea becomes ubiquitous—“AI will change everything,” “There’s a housing shortage forever”—pause. Ask: What is the underlying, measurable assumption here? How could it be wrong? Separate the plausible future from the certain present embedded in the price.

2. Create a “Pre-Mortem” for Popular Trades.

Before considering an investment that “everyone” is talking about, conduct a pre-mortem: Assume it is five years from now and this investment has failed. Write down the three most likely reasons why. This forces analytical thinking before emotional commitment.

3. Define Your Own “Circle of Competence” and Stay Within It.

The herd often runs into territories nobody understands (complex derivatives in 2007, tokenomics in 2021). Warren Buffett’s rule is to stay within his “circle of competence.” If you cannot explain how an asset creates economic value in simple terms, your investment is based on hope, not analysis—and hope is contagious in a herd.

4. Seek Disconfirming Evidence Deliberately.

Our natural bias is to seek information that confirms what the herd believes. Actively seek out well-reasoned, critical perspectives. Read the skeptics. If you cannot find a coherent bear case, you are not looking hard enough—or the narrative has become so dominant that dissent is suppressed, which is itself a danger signal.

5. Use the “Newspaper Headline” Test.

Imagine the investment you are about to make is the subject of a glowing front-page article in a major newspaper. Does that make you more confident or more nervous? In bubbles, positive media coverage is often a lagging indicator, a sign that the herd is already large and the easy money has been made.

6. Normalize the Feeling of Being Alone.

Practice making small, non-financial decisions against mild social pressure. It builds the “muscle memory” for tolerating the discomfort of dissent. Recognize that in investing, being lonely is often a prerequisite for being right. The two are not the same, but they are frequently correlated at extremes.

Conclusion: The Calm Confidence of Independent Thinking

The herd instinct isn’t something to fight—it’s something to understand. It makes us feel safe and excited at the same time, which can cloud our judgment. This tutorial isn’t about ignoring others’ opinions; sometimes the crowd is right. But in extreme markets, following the herd often moves money from the emotional to the disciplined.

True independence in investing isn’t about always going against the crowd—it’s about knowing when to join and when to step back. Sometimes participating early can be profitable, but emotional decisions made at the peak are dangerous. Sometimes you’ll be wrong alone, but that’s better than being wrong with the crowd. As you invest, you’ll feel the pull of fear and greed many times. Each time, you can either follow it blindly or step back and observe it as a psychological pattern.

The best investors aren’t those who never feel the urge to follow—they’re those who notice it, understand why it happens, and pause before acting. In that pause lies the foundation of lasting financial confidence.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.