Last Updated: February 2, 2026 at 10:30

Why Most Investors Underperform the Market: The Hidden Psychology of Financial Decisions - Investing Wisdom Series

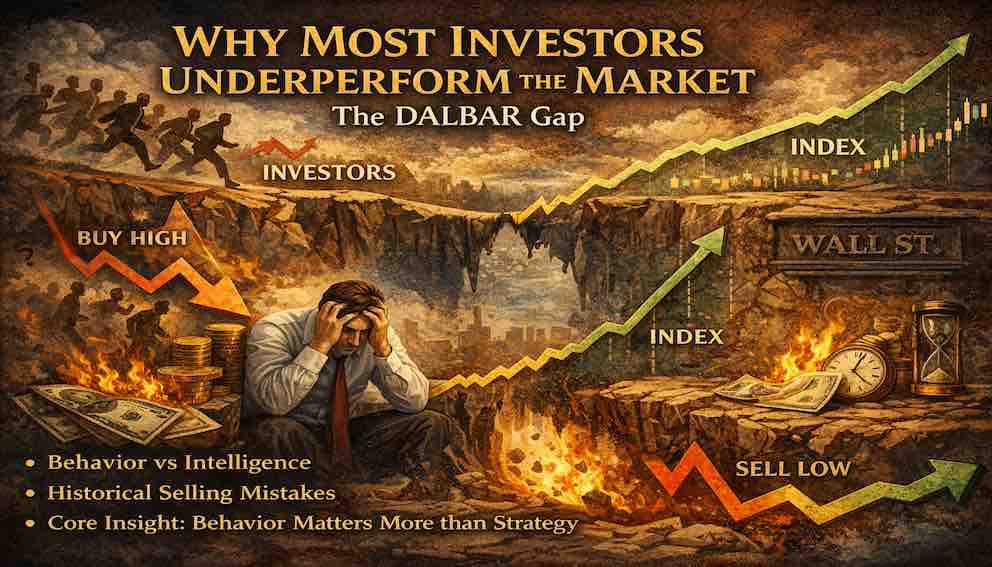

Intelligence alone doesn’t make someone a successful investor. Most investors lag behind the market not because they pick bad stocks, but because they let fear and greed guide their decisions. This tutorial explores why behavior matters more than strategy, using historical evidence, psychology, and real-life examples.

A Contradiction That Demands Explanation

There exists a curious contradiction in the world of investing, one that becomes more puzzling the longer we consider it. On one side, we have markets that, over extended periods, have demonstrated a persistent upward trajectory. The American stock market, for instance, has delivered approximately ten percent annual returns across the better part of a century, through wars, depressions, and innumerable crises. The mathematics are clear and compelling.

On the other side, we have the individual investor. The person who studies, saves, and earnestly attempts to participate in this growth. The data concerning their results, however, tells a different and more sobering story.

Research conducted by the firm Dalbar, which has tracked investor behavior for decades, reveals a consistent and significant gap. While the market itself may grow at a certain rate, the average investor in equity funds captures only a fraction of that return. The gap is not small—it often measures several percentage points annually. Over twenty or thirty years, such a difference does not merely reduce wealth; it can transform what might have been financial security into something far less substantial.

The question, then, is not whether this gap exists. The evidence is clear that it does. The real question is why.

Why do individuals, acting with intelligence and intention, consistently achieve results so far below what the market itself provides? The answer, it turns out, has very little to do with intelligence, and almost everything to do with human nature.

The Market as a Mirror

To understand why investors often underperform, we need to rethink what the “market” really is. Many people talk about the market as if it’s a machine—a system with its own rules and predictable patterns. That’s only partly true.

At its core, the market is a crowd. It’s made up of millions of people, each making decisions based on what they know, what they think, and—most importantly—how they feel.

The price of a stock or bond at any moment isn’t just about numbers or earnings. It’s the point where fear and greed, hope and worry, optimism and pessimism balance out for the time being. In other words, the market doesn’t just reflect economic facts—it reflects human emotions. It shows what we collectively feel about the present and what we hope for in the future.

When we invest, we’re not entering a purely logical system. We’re stepping into a world shaped by human psychology. And we carry with us mental shortcuts and emotional instincts that helped our ancestors survive but can actually hurt us in the financial world. In markets, these natural tendencies—like reacting to fear or chasing rewards—often lead to costly mistakes.

If you’re interested in going deeper on why smart investors still make emotional decisions, check out the tutorial “Why Smart Investors Still Make Emotional Mistakes: The Hidden Role of Emotions in Money Decisions” in the Behavioral Finance series here.

The Psychology of Loss

Consider one of the most robust findings from behavioral psychology: loss aversion. The psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky demonstrated that for most people, the pain of losing a sum of money is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining the same amount. This is not a logical calculation. It is a deep, visceral reaction.

In the natural world, this bias makes excellent sense. If you are foraging for food, the potential loss of your existing supplies is a matter of survival. The potential gain of a little more is merely a matter of comfort. The evolutionary wiring is clear: avoid catastrophic loss first, seek incremental gain second.

But in the financial markets, this wiring creates a profound distortion. A market decline of ten percent does not represent a "loss" in the same sense as losing your wallet. It is a paper fluctuation, a change in quoted value that may or may not become permanent. Yet, our ancient neural circuitry does not make this distinction. The red numbers on a screen trigger the same primal alarm bells that might have warned our ancestors of a dwindling food store.

The result is a powerful, often overwhelming, urge to act. To stop the bleeding. To sell the declining asset and move to safety. This urge feels like prudence. It feels like taking control of a dangerous situation. But in the context of long-term investing, it is often the precise action that converts a temporary market fluctuation into a permanent financial loss.

The Narrative of Fear and Greed

Our psychology is also shaped by stories. We are narrative creatures. We understand the world through cause and effect, through heroes and villains, through dramatic arcs. The financial media, which exists to capture our attention, feeds this appetite relentlessly.

A market decline is never presented as a statistical probability within a long-term trend. It is a "rout," a "collapse," a "panic." It comes with headlines in bold type and photographs of worried traders. The narrative is one of crisis and urgency. Similarly, a market rise is a "surge," a "rally," a "melt-up." It is framed as an opportunity that must be seized before it disappears.

These narratives are compelling because they align with our innate love of drama. They make the impersonal machinations of finance feel immediate and human. But they also create a powerful emotional rollercoaster. They amplify our natural loss aversion during declines and stimulate a fear of missing out during advances.

The individual investor, absorbing this daily narrative, is subjected to a constant pull between two poles: the fear of losing what they have, and the greed of gaining what others seem to be getting. The logical, long-term plan they may have constructed in a moment of calm is steadily eroded by this daily tide of emotion-laden storytelling.

If you want to understand the market psychology of fear and greed, read our Market Psychology chapter here.

The Illusion of Activity

Compounding this problem is our cultural bias toward action. In most realms of life, facing a problem means devising a solution and implementing it. Passivity is often seen as neglect. If your car makes a strange noise, you take it to a mechanic. If a storm is coming, you board up the windows.

This bias transfers seamlessly to investing. When the market falls, the logical impulse is to do something. To adjust, to reposition, to respond to the new information. To simply sit and watch the value of your holdings decline feels, at a deep level, like negligence. It feels like you are not doing your job as a steward of your capital.

Yet, in the long history of markets, the single most beneficial response to a broad decline has often been patient inaction. The declines have, without exception, been followed by recoveries. The investor who could withstand the psychological discomfort of passivity, who could ignore the compelling narrative of crisis and the innate urge to act, was rewarded. The investor who "fixed the noise" by selling, however, often found they had repaired nothing and had instead locked in a loss.

The great irony is that the most sophisticated activity—the complex analysis, the tactical shifts, the attempts to time the market—often produces worse results than simple, patient inaction. The activity provides the psychological comfort of control, but it frequently comes at a tremendous financial cost.

A Different Kind of Discipline

If the primary obstacles are psychological, then the solution must also be psychological. It requires a different kind of discipline. Not the discipline of more analysis or more frequent action, but the discipline of restraint. The discipline to distinguish between a real threat to a company's fundamental value and a temporary shift in crowd sentiment. The discipline to recognize the emotional pull of a market narrative without being compelled by it.

This discipline is often best achieved not through sheer willpower in the moment of crisis, but through structure created in advance. It is the discipline of constructing a simple, sensible plan—one based on broad diversification, awareness of costs, and a realistic time horizon—and then building mechanisms that help you adhere to it.

These mechanisms can be profoundly simple. Automating contributions so that buying happens consistently, regardless of market mood. Adopting a portfolio that requires minimal maintenance and adjustment. Writing down, in clear language, what you believe and how you will respond to certain market conditions, and then reviewing those words when emotion runs high.

The goal of these structures is not to maximize theoretical returns. The goal is to minimize the number of times you must rely on flawless emotional control in the face of powerful psychological storms. They are guardrails, not engines.

The Liberating Perspective

Understanding this can be surprisingly freeing. The pressure to be smarter, know more, or outthink everyone else begins to lift. In its place comes a new challenge: self-awareness—learning how your own emotions and habits affect your financial decisions and building a plan that works with them instead of against them.

You start seeing financial news differently. Instead of urgent commands, it becomes a window into how the crowd feels. A market panic stops feeling like a personal threat and starts looking like a display of fear. A big rally stops feeling like a missed opportunity and becomes a show of greed. You shift from being swept up in the mood to watching the crowd from the sidelines.

This doesn’t guarantee higher returns—nothing can—but it gives you an advantage. By avoiding the behavioral traps that trip up most investors, you’re more likely to capture the long-term growth the market provides.

The performance gap isn’t a mystery or a failure—it’s the natural result of our human psychology meeting the emotional swings of the market. Closing the gap doesn’t start with picking a better stock or predicting the economy. It starts with looking honestly at yourself and building a strategy that fits the investor you really are.

The most important investment you’ll ever make isn’t in a stock or fund. It’s in understanding the investor in the mirror and creating a plan they can actually follow, even on the hardest days. That’s where true financial discipline lives—and that’s how the gap between hope and reality begins to close.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.